Scientists Tell Us What Would Happen If North Korea Detonated a Hydrogen Bomb Underwater

Credit to Author: Caroline Haskins| Date: Tue, 26 Sep 2017 16:00:00 +0000

On Thursday evening, North Korean Foreign Minister Ri Yong-ho told South Korean news agency Yonhap that Kim Jong-un is considering testing a hydrogen bomb in the Pacific Ocean as a response to President Trump’s threat “to totally destroy North Korea.”

“It could be the most powerful detonation of a hydrogen bomb in the Pacific,” Ri told Yonhap. “We have no idea about what actions could be taken, as it will be ordered by leader Kim Jong-un.”

By saying “in the Pacific” rather than “over the Pacific,” Ri suggests the detonation would be underwater rather than in the air.

As you may have noticed, tension between North Korea and the US has been rising by the day; the US is currently flying bomber planes near the country as a display of force.

Ri said on Saturday morning that a strike against the US mainland is “inevitable,” and just after midnight on Sunday, Trump threatened North Korea again on Twitter.

If North Korea detonated a hydrogen bomb in the Pacific, what would happen? Should Hawaii, California, and Japan expect hydrogen bomb tsunamis or radioactive storms? Will marine life suffer a massive die-off or become radioactive?

I spoke with a few experts to gather an idea of what we could expect from an underwater hydrogen bomb detonation, and what the implications are.

—

WAVES

Oliver Bühler, a professor of applied mathematics at NYU who studies fluid dynamics, told me that we can definitely expect waves from an underwater hydrogen bomb detonation.

“An underwater explosion or an above ground explosion would clearly create a bunch of waves, strong waves,” he said.

These waves have been created in underwater nuclear tests before. But the weapons contained just a fraction of the power in North Korea’s hydrogen bomb, and the tests were still incredibly dangerous. During Operation Crossroads in 1946, a poorly calculated safe observable distance from a 23-kiloton nuclear blast drenched American soldiers in toxic levels of radiation. The exposure is estimated to have shortened the lifespan of each witness by about three months.

However, mathematical analysis provides a safer, clearer picture of what’s happening in the water.

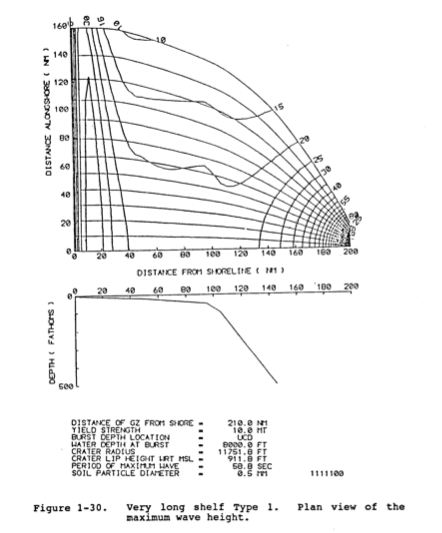

One of the most comprehensive analyses is a 400-page-long US military report written in 1996 by Bernard Le Mehaute and Shen Wang of the Rosenstiel School of Marine & Atmospheric Science.

After detonation, we can expect a shockwave radiating outward and carrying upwards of 140 kilotons of energy. According to US intelligence, North Korea’s most recent hydrogen bomb test on September 3 yielded approximately this much force. For reference, the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki carried 15 and 21 kilotons of energy, respectively.

As the shock wave occurs, plasma unleashes into the water, sending massive amounts of water vapor and miscellaneous debris into the air.

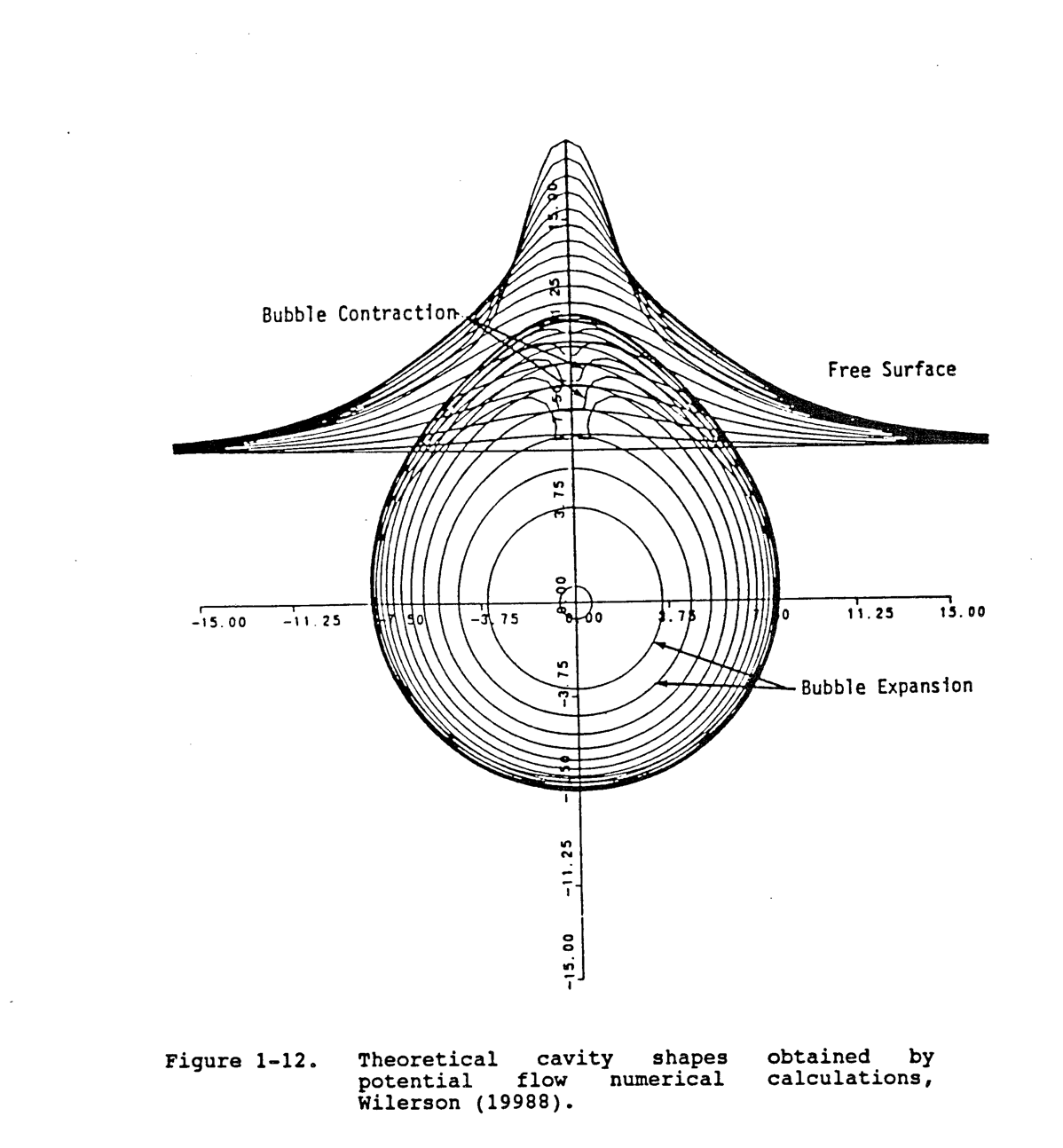

The water expands radially, forming a bubble that surges above the water surface. But due to its colossal size, a chasm known as a “re-entrant jet” forms in the middle of the bubble and it collapses in on itself. As the bubble falls to the water surface, a column of water shoots up into the air, which disintegrates into a series of waves.

The shockwave and radioactive energy would kill just about all marine life in the immediate area. After a nuclear bomb test in 1946, scientists were able to pull 38,000 dead fish from the water.

However, Bühler said that the waves would not be capable of creating a tsunami.

He told me that the waves in this document carry just a fraction of the energy generated by a tsunami, which necessitates a disturbance site hundreds of miles long

“A bomb like this would act more like a storm,” Bühler said. “It would create tons of waves, but these waves would disperse out. The energy doesn’t arrive all in one big bang like a tsunami. It arrives over hours, days, sometimes weeks.”

—

WEATHER

If waves and storms disperse from the site of the explosion, should we be worried about radioactive rain on Pacific islands like Hawaii? According to oceanographer Matthew Charette, who studies the effect of radionuclides on marine chemistry, these storms are not likely in the aftermath of a nuclear test.

He told me that when nuclear energy mixes with trace elements in seawater, like sodium and chloride, the elements become radioactive. But the damage that these elements can do depends on their chemical behavior.

“Some [elements] are very insoluble—they’ll stick to elements and particles in the water column, settle into the local sediment, and they won’t be an issue in the far field,” Charette said. “Other elements are more soluble in seawater, like Cesium 137 from the Fukushima disaster. That can move with ocean currents.”

Charette said that due to the tremendous volume of the ocean, the radioactive elements would be too weakly concentrated in the water to pose a severe weather threat.

“For an underwater test, I wouldn’t be concerned very much at all,” he said. “The dilution factors would be immense.”

However, Ken Buesseler, a senior scientist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, told me that he has concerns—even if the underwater detonation takes place far from a landmass.

Buesseler said that radioactive water from a detonation will definitely enter Pacific Ocean currents, but after that, it’s extremely difficult to predict where the water will flow.

“[Radiation] wouldn’t stay in one place like in a reactor accident—it would move with the ocean currents,” he said. “You could detonate something near an island, and the currents carry it offshore pretty quickly. Or you could detonate something further out and the currents bring it in shore. It’s very hard to predict how it would affect an inhabited island.”

But different currents circulate on timescales that vary from weeks to millennia, so Buesseler said that it’s almost impossible to predict when this water could make landfall.

Basically, we have no idea which places could be affected, and how long it would take for radiation to show up there.

—

LIFE

Charette and Buesseler told me that earlier this year, they went to Bikini Atoll—a subset of islands within the Marshall Islands that were the site of 23 American nuclear detonation tests between 1946 and 1958.

More than 70 years later, Bikini Atoll has still not completely recovered. Radiation levels on one of Bikini Atoll’s islands still exceeds the safe radiation standards set by the US and the Marshall Islands.

Read More: After 70 Years of Nuclear Fallout, Will Bikini Atoll Ever Be Safe Again?

When Charette and Buesseler visited, they focused on measuring radioactivity found in seawater, groundwater, and seafloor samples. While the results of their study haven’t been published yet, Charette said he was pleasantly surprised by what he saw.

“I was impressed with how the islands have recovered,” he said. “At least in terms of flora and fauna.”

Other scientists have also found that marine life has largely rebounded since nuclear fallout. Stanford University professor Stephen Palumbi and graduate student Elora López found that corals have actually adapted to high levels of radiation.

A 2008 Bikini Atoll biodiversity survey found that while 70 percent of coral species have rebounded since nuclear testing. However, it took decades for this recovery to happen, and under current conditions, the same recovery rate may not be possible.

“If the disturbance event were to be repeated in the modern day, recovery would not be expected to be as high, due to the combination of additional stressors associated with climate change, and a possibly much altered atoll environment due to an additional 50 years of human occupation,” the study reads.

Charette said that although marine life made a recovery in Bikini Atoll, the biological effects of a nuclear detonation shouldn’t be dismissed—and remember, roughly 70 years after those tests, the area has not seen a complete recovery yet.

“The thing you have to be concerned about is radioactive products in the seafood supply,” he said. “Especially in seafood that’s caught in a region close by any potential test.”

These thoughts were echoed by Buesseler.

“As human consumers of fish, we would internalize [radioactive] isotopes,” he told me. “In that case, you’d be concerned about location [of the detonation]. A fishing ground might have to be shut down because of local contamination.”

However, Buesseler believes that the biggest human risk from nuclear testing is psychological.

“You put radiation anywhere, and people will immediately change their habits—from the fish they eat, to where they might wanna go swimming,” he said. “These things might not be supported by science, but cause panic. Then, of course, there’s anxiety that the next one might be in a populated area.”

—

In their conversations with me, Bühler, Charette, and Buesseler all stressed how difficult it is to predict the long term consequences of nuclear detonation testing.

When I spoke to Bühler about the 400-page document “Water Waves Generated by Underwater Explosions,” he said that reports like it used to be very common.

“In the hot days of US bomb testing, we were worried about all kinds of questions,” he said. “When we explode the bombs, will it cause a tsunami, or set the atmosphere on fire?’ Basically, all these studies showed that is not something that is going to happen. But that in some sense encouraged people to go, ‘Oh, let’s just drop the bomb and test it.'”

Bühler said that after science suggested there was no risk of immediate violence or catastrophe, people adopted a more blasé stance toward nuclear testing. The US only banned nuclear weapons testing in 1992—decades after negotiations began.

“It was only slowly realized that what we can’t control is what happens years and years afterwards,” he said. “That’s the main reason why it’s not responsible to do these tests. The short term consequences people can figure out. But what happens the next year and after that—no one has control over. “