Supply Chain Security is the Whole Enchilada, But Who’s Willing to Pay for It?

Credit to Author: BrianKrebs| Date: Fri, 05 Oct 2018 19:45:18 +0000

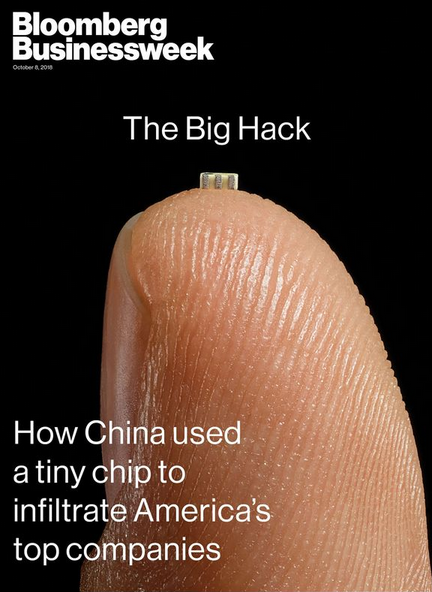

From time to time, there emerge cybersecurity stories of such potential impact that they have the effect of making all other security concerns seem minuscule and trifling by comparison. Yesterday was one of those times. Bloomberg Businessweek on Thursday published a bombshell investigation alleging that Chinese cyber spies had used a U.S.-based tech firm to secretly embed tiny computer chips into electronic devices purchased and used by almost 30 different companies. There aren’t any corroborating accounts of this scoop so far, but it is both fascinating and terrifying to look at why threats to the global technology supply chain can be so difficult to detect, verify and counter.

In the context of computer and Internet security, supply chain security refers to the challenge of validating that a given piece of electronics — and by extension the software that powers those computing parts — does not include any extraneous or fraudulent components beyond what was specified by the company that paid for the production of said item.

In the context of computer and Internet security, supply chain security refers to the challenge of validating that a given piece of electronics — and by extension the software that powers those computing parts — does not include any extraneous or fraudulent components beyond what was specified by the company that paid for the production of said item.

In a nutshell, the Bloomberg story claims that San Jose, Calif. based tech giant Supermicro was somehow caught up in a plan to quietly insert a rice-sized computer chip on the circuit boards that get put into a variety of servers and electronic components purchased by major vendors, allegedly including Amazon and Apple. The chips were alleged to have spied on users of the devices and sent unspecified data back to the Chinese military.

It’s critical to note up top that Amazon, Apple and Supermicro have categorically denied most of the claims in the Bloomberg piece. That is, their positions refuting core components of the story would appear to leave little wiggle room for future backtracking on those statements. Amazon also penned a blog post that more emphatically stated their objections to the Bloomberg piece.

Nevertheless, Bloomberg reporters write that “the companies’ denials are countered by six current and former senior national security officials, who—in conversations that began during the Obama administration and continued under the Trump administration—detailed the discovery of the chips and the government’s investigation.”

The story continues:

Today, Supermicro sells more server motherboards than almost anyone else. It also dominates the $1 billion market for boards used in special-purpose computers, from MRI machines to weapons systems. Its motherboards can be found in made-to-order server setups at banks, hedge funds, cloud computing providers, and web-hosting services, among other places. Supermicro has assembly facilities in California, the Netherlands, and Taiwan, but its motherboards—its core product—are nearly all manufactured by contractors in China.

Many readers have asked for my take on this piece. I heard similar allegations earlier this year about Supermicro and tried mightily to verify them but could not. That in itself should be zero gauge of the story’s potential merit. After all, I am just one guy, whereas this is the type of scoop that usually takes entire portions of a newsroom to research, report and vet. By Bloomberg’s own account, the story took more than a year to report and write, and cites 17 anonymous sources as confirming the activity.

Most of what I have to share here is based on conversations with some clueful people over the years who would probably find themselves confined to a tiny, windowless room for an extended period if their names or quotes ever showed up in a story like this, so I will tread carefully around this subject.

The U.S. Government isn’t eager to admit it, but there has long been an unofficial inventory of tech components and vendors that are forbidden to buy from if you’re in charge of procuring products or services on behalf of the U.S. Government. Call it the “brown list, “black list,” “entity list” or what have you, but it’s basically an indelible index of companies that are on the permanent Shit List of Uncle Sam for having been caught pulling some kind of supply chain shenanigans.

More than a decade ago when I was a reporter with The Washington Post, I heard from an extremely well-placed source that one Chinese tech company had made it onto Uncle Sam’s entity list because they sold a custom hardware component for many Internet-enabled printers that secretly made a copy of every document or image sent to the printer and forwarded that to a server allegedly controlled by hackers aligned with the Chinese government.

That example gives a whole new meaning to the term “supply chain,” doesn’t it? If Bloomberg’s reporting is accurate, that’s more or less what we’re dealing with here in Supermicro as well.

But here’s the thing: Even if you identify which technology vendors are guilty of supply-chain hacks, it can be difficult to enforce their banishment from the procurement chain. One reason is that it is often tough to tell from the brand name of a given gizmo who actually makes all the multifarious components that go into any one electronic device sold today.

Take, for instance, the problem right now with insecure Internet of Things (IoT) devices — cheapo security cameras, Internet routers and digital video recorders — sold at places like Amazon and Walmart. Many of these IoT devices have become a major security problem because they are massively insecure by default and difficult if not also impractical to secure after they are sold and put into use.

For every company in China that produces these IoT devices, there are dozens of “white label” firms that market and/or sell the core electronic components as their own. So while security researchers might identify a set of security holes in IoT products made by one company whose products are white labeled by others, actually informing consumers about which third-party products include those vulnerabilities can be extremely challenging. In some cases, a technology vendor responsible for some part of this mess may simply go out of business or close its doors and re-emerge under different names and managers.

Mind you, there is no indication anyone is purposefully engineering so many of these IoT products to be insecure; a more likely explanation is that building in more security tends to make devices considerably more expensive and slower to market. In many cases, their insecurity stems from a combination of factors: They ship with every imaginable feature turned on by default; they bundle outdated software and firmware components; and their default settings are difficult or impossible for users to change.

We don’t often hear about intentional efforts to subvert the security of the technology supply chain simply because these incidents tend to get quickly classified by the military when they are discovered. But the U.S. Congress has held multiple hearings about supply chain security challenges, and the U.S. government has taken steps on several occasions to block Chinese tech companies from doing business with the federal government and/or U.S.-based firms.

Most recently, the Pentagon banned the sale of Chinese-made ZTE and Huawei phones on military bases, according to a Defense Department directive that cites security risks posed by the devices. The U.S. Department of Commerce also has instituted a seven-year export restriction for ZTE, resulting in a ban on U.S. component makers selling to ZTE.

Still, the issue here isn’t that we can’t trust technology products made in China. Indeed there are numerous examples of other countries — including the United States and its allies — slipping their own “backdoors” into hardware and software products.

Like it or not, the vast majority of electronics are made in China, and this is unlikely to change anytime soon. The central issue is that we don’t have any other choice right now. The reason is that by nearly all accounts it would be punishingly expensive to replicate that manufacturing process here in the United States.

Even if the U.S. government and Silicon Valley somehow mustered the funding and political will to do that, insisting that products sold to U.S. consumers or the U.S. government be made only with components made here in the U.S.A. would massively drive up the cost of all forms of technology. Consumers would almost certainly balk at buying these way more expensive devices. Years of experience has shown that consumers aren’t interested in paying a huge premium for security when a comparable product with the features they want is available much more cheaply.

Indeed, noted security expert Bruce Schneier calls supply-chain security “an insurmountably hard problem.”

“Our IT industry is inexorably international, and anyone involved in the process can subvert the security of the end product,” Schneier wrote in an opinion piece published earlier this year in The Washington Post. “No one wants to even think about a US-only anything; prices would multiply many times over. We cannot trust anyone, yet we have no choice but to trust everyone. No one is ready for the costs that solving this would entail.”

The Bloomberg piece also addresses this elephant in the room:

“The problem under discussion wasn’t just technological. It spoke to decisions made decades ago to send advanced production work to Southeast Asia. In the intervening years, low-cost Chinese manufacturing had come to underpin the business models of many of America’s largest technology companies. Early on, Apple, for instance, made many of its most sophisticated electronics domestically. Then in 1992, it closed a state-of-the-art plant for motherboard and computer assembly in Fremont, Calif., and sent much of that work overseas.

Over the decades, the security of the supply chain became an article of faith despite repeated warnings by Western officials. A belief formed that China was unlikely to jeopardize its position as workshop to the world by letting its spies meddle in its factories. That left the decision about where to build commercial systems resting largely on where capacity was greatest and cheapest. “You end up with a classic Satan’s bargain,” one former U.S. official says. “You can have less supply than you want and guarantee it’s secure, or you can have the supply you need, but there will be risk. Every organization has accepted the second proposition.”

Another huge challenge of securing the technology supply chain is that it’s quite time consuming and expensive to detect when products may have been intentionally compromised during some part of the manufacturing process. Your typical motherboard of the kind produced by a company like Supermicro can include hundreds of chips, but it only takes one hinky chip to subvert the security of the entire product.

Also, most of the U.S. government’s efforts to police the global technology supply chain seem to be focused on preventing counterfeits — not finding secretly added spying components.

Finally, it’s not clear that private industry is up to the job, either. At least not yet.

“In the three years since the briefing in McLean, no commercially viable way to detect attacks like the one on Supermicro’s motherboards has emerged—or has looked likely to emerge,” the Bloomberg story concludes. “Few companies have the resources of Apple and Amazon, and it took some luck even for them to spot the problem. ‘This stuff is at the cutting edge of the cutting edge, and there is no easy technological solution,’ one of the people present in McLean says. ‘You have to invest in things that the world wants. You cannot invest in things that the world is not ready to accept yet.’”

For my part, I try not to spin my wheels worrying about things I can’t change, and the supply chain challenges definitely fit into that category. I’ll have some more thoughts on the supply chain problem and what we can do about it in an interview to be published next week.

But for the time being, there are some things worth thinking about that can help mitigate the threat from stealthy supply chain hacks. Writing for this week’s newsletter put out by the SANS Institute, a security training company based in Bethesda, Md., editorial board member William Hugh Murray has a few provocative thoughts:

- Abandon the password for all but trivial applications. Steve Jobs and the ubiquitous mobile computer have lowered the cost and improved the convenience of strong authentication enough to overcome all arguments against it.

- Abandon the flat network. Secure and trusted communication now trump ease of any-to-any communication.

- Move traffic monitoring from encouraged to essential.

- Establish and maintain end-to-end encryption for all applications. Think TLS, VPNs, VLANs and physically segmented networks. Software Defined Networks put this within the budget of most enterprises.

- Abandon the convenient but dangerously permissive default access control rule of “read/write/execute” in favor of restrictive “read/execute-only” or even better, “Least privilege.” Least privilege is expensive to administer but it is effective. Our current strategy of “ship low-quality early/patch late” is proving to be ineffective and more expensive in maintenance and breaches than we could ever have imagined.