Russia-Ukraine war: related cyberattack developments

Credit to Author: Chester Wisniewski| Date: Mon, 21 Mar 2022 08:15:48 +0000

On February 22, 2022, Sophos published an article looking at Russia’s history of cyberattacks during times of conflict and geopolitical tension. This companion article tracks what is currently unfolding related to the Russia-Ukraine war. Some of the news is clouded through the inevitable “fog of war” making accurate attribution or factual confirmation more difficult, and there can be a time delay before some news emerges from the war zone. The content included here represents Sophos’ best understanding of the facts at the time of publication.

[Update (2022-03-17)]: On Tuesday, March 15, Joseph Cox at Vice reported that Ukraine had detained a malicious insider who was allegedly providing technical assistance to Russian troops by routing calls for them and sending SMS text messages to Ukrainian troops suggesting they surrender.

In a follow-up to this weekend’s update, Raphael Satter at Reuters reported that a Ukrainian cybersecurity official had disclosed in a statement that the Viasat satellite outage as the invasion begun was a “really huge loss in communications in the very beginning of war.”

On Wednesday, March 16, a social engineering approach appeared to succeed for Ukrainian newspaper Ukrainska Pravda, when it crafted a phish to determine if the Head of the Chechen Republic, Kadyrov, was in Ukraine as he claimed. The paper sent him a Telegram message saying it wanted to share a draft of a story for review, with a link. When he clicked the link to view the document, the paper logged his IP address and confirmed he was not in fact in Ukraine, but rather in Grozny.

Attacks supporting the war are still occurring online, but they remain mostly confined to Ukraine. The State Service of Special Communication and Information Protection of Ukraine released a statement noting that attacks have not abated and that they’ve weathered more than 3,000 DDoS attacks, with a peak of 275 DDoS attacks in a single day. The worst attack peaked at more than 100 Gbps.

Lastly, there appears to be a supply chain attack of the Node.js package repository, NPM. The authors updated the code to behave maliciously in Russia and Belarus. They later changed the code to leave an anti-war note on the desktop of every computer it executes on, along with some lyrics and a link to a YouTube video. This could cause massive problems for applications that don’t do a pre-install security review of updated components, as the affected components are downloaded over one million times a week. Unfortunately, such actions can result in a reluctance to update software packages, making millions of people less secure.

[Update (2022-03-15)]: From March 7, we began to see more information about the disruption to Viasat’s satellite service in Central and Eastern Europe (mentioned above on March 6.) Two reports were published speculating that a particular brand of modem used with the satellite downlinks had its firmware corrupted or had been sent management commands to disable them. On Friday, March 11, Reuters reported that Viasat had confirmed the firmware theory and that the US NSA, French ANSSI, and Ukrainian intelligence were looking into the attack.

On Saturday, March 12, CNN reported that there had been a dramatic rise in downloads of VPN software originating from Russia since the government began banning popular social media services like Twitter, Facebook and Instagram. Similar reports emerged for the use of secure messaging applications like Signal, and the Tor Browser. To evade blocking, many Tor users rely on a technology called Snowflake. The authors of Snowflake are encouraging others to participate as proxies to evade government blocks in Russia and other internet-censored states.

Kim Zetter wrote a great piece for Politico on March 12, and interviewed many former US government hackers and officials about the risk of escalation in nation-state attacks related to the war. Their conclusions are informed and similar to my own, which is that we shouldn’t expect directly attributable attacks from either side outside of the area of conflict. The bigger concern is that activity by civilian hacktivists or vigilantes might cause escalation due to the “fog of cyberwar” making it hard to tell if it is the US, Russia, or someone more anonymous.

As predicted, attacks from alleged hackivist groups are starting to create even more confusion and tension. Die Welt reported on Sunday, March 13 that the Russian oil giant Rosneft’s German subsidiary was inaccessible and that operations were partially disrupted. Disruption to Rosneft, part of the critical infrastructure in Germany responsible for keeping people warm in winter, is unlikely to go down well with the BSI.

Two more malware attacks against Ukrainian targets were discovered on Monday, March 14, neither of which has so far been positively attributed, but both fitting in with support for Russia’s goals. Bleeping Computer wrote about a phishing attack that delivered both a Cobalt Strike beacon and an additional piece of malware that looks like an information stealer and downloader. ESET discovered another wiper malware called CaddyWiper that seemingly had very limited distribution. It did not resemble the previous wipers, but, similar to the last one, was deployed using group policy objects (GPOs) and attempted to preserve the attacker’s foothold within the victim’s network.

There were also reports over the weekend and into March 14 that some bug bounty programs, in particular HackerOne, were restricting access to payouts for participants in Ukraine. As the day unfolded, Zack Whittaker from Tech Crunch got a statement from the CTO, Alex Rice, stating that they were sorting out the issues and they were due to sanctions on the eastern separatist provinces and that other Ukrainian hackers would be reimbursed. Turns out sanctions are harder to apply than it may appear.

[Update (2022-03-11)]: Raphael Satter at Reuters (@razhael) has been a great resource for cyber-related Ukraine news and on March 9, he reported on Ukraine’s move of its data centers outside of the country to maintain their access and availability. A similar plan was put in place in Estonia during the Russian DDoS attacks (referenced earlier in this post.) In the Estonian case it was mostly related to websites, while Satter’s report seems to be more concerned with the security of government data as a whole.

After calls for the formation of an “IT army” by Ukraine’s deputy prime minister, it appears that many people scrambled to acquire “hacking tools” to assist in the fight. Inevitably, as discovered by Cisco’s Talos group, someone booby-trapped the tool downloads by installing an information stealer. Initial analysis appears to show that the Trojan tool distributed via Telegram chat groups steals passwords, cookies, and cryptocurrency wallets.

Thomas Brewster, another authoritative journalist covering cyber conflict, for Forbes, is reporting on an alleged data breach at Roskomnadzor, the Kremlin’s internet censor. While the leaked information is interesting; if true, it could be useful in informing Russian citizens of what types of information have been removed from their media diet.

Finnish flights to a city near its border with Russia were cancelled on March 8 until at least March 16, due to alleged jamming of GPS signals (link in Finnish) by the Russian Federation. Finland responded appropriately for the safety of civilian aviation. However, this is a concerning development that could threaten the safety of non-participants in the war.

Brewster also reports that Ukrainian internet provider Triolan has been repeatedly hacked since the invasion began. The initial attacks coincided with the invasion on February 24, and were repeated on March 9, this time resetting routers and other infrastructure to factory defaults. Some devices cannot be configured remotely and may remain offline for some time due to the physical danger of accessing parts areas of Ukraine that are under active attack. This is a great reminder of the “fog of war” related to cyber activities during times of intense conflict. We often only hear details days or weeks after the actual events as communications are disrupted and prioritized for other more urgent reporting.

[Update (2022-03-08)]: Tuesday, March 8 was International Women’s Day. According to a tweet from Tarah Wheeler (@tarah), it appears that hacktivist activities against the rail systems in Belarus resulted in disruption and delays to Russian forces en route to the Ukrainian front. (Tarah’s work in cyber security is important and she’s well worth a follow.)

It also appeared that Russia’s secure communications technology, Era, is reliant on 3G/4G cellular networks, which have been disabled or compromised during the invasion, preventing soldiers from communicating securely without being surveilled. Secure communications are hard and it’s even harder when you are overly dependent on modern technology to make it work.

Reuters reported that EU telecoms ministers were meeting in Nevers, France to discuss the creation of a cybersecurity emergency response fund to help organizations disabled through cyber attacks. This appears to be prompted by the wiper attacks in Ukraine we reported on earlier in this post.

There were also reports of ransomware crews experiencing supply chain delays/issues due to the war in Ukraine. Brett Callow is probably correct in that in the short term we may experience a brief reprieve due to reorganizations after the Conti leaks as well as disrupted internet connections and sanctions against the Russian Federation.

[Update (2022-03-06)]: It continued to be a quiet time on the cyber front in the war in Ukraine. However, there were two significant updates over the weekend of March 5 to March 6.

First, beginning on February 24, customers of ViaSat in Central and Eastern Europe began experiencing disruptions and outages to their satellite internet service. On Saturday, March 5, a story in Germany’s Spiegel seemed to confirm suspicions (in German) that the outages were due to a booby-trapped firmware update that “bricked” the modems of downlinks causing permanent disablement until the affected units were replaced.

This was a significant finding. This service is reported to be used heavily by Ukrainians for internet access, as well as by the Ukrainian military, which seems to point the finger at the Russian security services. Further, the issue disabled communications with thousands of windmills in Germany, preventing their direct control by the energy company responsible for their management.

The problem? Attribution in cyber attacks. Attribution is hard at the best of times, and it is easy to draw conclusions that are incorrect before all the relevant evidence can be gathered. While the German security services seem confident that the incident is related to the war, it is far from solid enough evidence to consider responsive action, if it was deemed appropriate. Cyber conflicts are affected by the “fog of war” far more than traditional operations. If this was a deliberate attack by Russia, it would be the first since the beginning of the war that has resulted in significant collateral damage.

On Sunday, March 6, Anonymous, the loosely organized hacker collective, claimed credit for hacking several Russian TV stations and causing their video streaming services to broadcast videos of the war, including the shelling of residential areas by invading Russian troops. While they posted this as “proof,” it has yet to be confirmed. The purported goal of the action was apparently to ensure Russian citizens are aware of the war and how it is being conducted.

[Update (2022-03-03)]: On Thursday, March 3, things continued to decelerate in the cyber realm, although that was not the case for the ground war. On the vigilante front we saw the emergence of a new Twitter account called @TrickbotLeaks that throughout the day doxed alleged members of the Trickbot, Conti, Mazo, Diavol, Ryuk and Wizard Spiders crime groups. Most of this activity seemed to stem from the Conti leaks earlier in the week. Vitali Kremez has an interesting analysis on his feed.

Brian Krebs suggested this activity might cause problems for cybercriminals who have been talking about getting out of Russia while the going was good. It certainly could be a challenging time to escape the grasp of the authorities if Europol suddenly had reasons to pursue indictments or warrants for arrest.

Further, websites of municipal and regional governments in Russia-seized territories in the south of Ukraine were commandeered or hacked to display fake news suggesting that the Zelensky government had capitulated and surrendered to Russian forces. This was countered by Ukraine’s Security Service of Ukraine (SSU).

[Update (2022-03-02)]: On Wednesday, March 2, things settled down in the cyber realm, but that didn’t mean activity necessarily slowed. As communications disruptions intensified due to the ground fighting, there was a time delay in learning effectively what was happening inside Ukraine.

Ciaran Martin, former head of the UK’s Nation Cyber Security Centre (NCSC), published a detailed expert analysis of the cyber landscape in Ukraine so far and explained his views on how we got to where we are and what might come next. We highly recommend this article.

The Conti saga continued with the group officially deleting its existing virtual infrastructure and allegedly starting again somewhere new. This is not the outcome many of us hoped for, but it remains to be seen whether the gang can pull it all back together again. The nursery rhyme, “All the king’s horses and all the king’s men,” comes to mind.

Additionally, the leaked Conti chat logs revealed the group had purchased a zero-day vulnerability in Internet Explorer 11 to use in attacks at the end of 2020. This could be the first and closest thing to evidence we have that these groups are willing to spend some of their ill-gotten gains on acquiring expensive and exclusive unpatched exploits to further their crimes.

[Update (2022-03-01)]: Fallout from the Conti breach by a Ukrainian researcher continued on Tuesday, March 1, with another dump comprising almost all inside communications, source code and other operational information and plans. It will likely take some time for all of this to be sorted through to determine its significance, but it is the best inside look we have ever had of how a large-scale criminal ransomware operation operates.

A ransomware crew on Twitter known as TheRedBanditsRU tweeted a statement distancing itself from the war and was quoted as saying “We do not respect Putin as #leader of #Russia.” The crew claims that it is not attacking Ukrainian civilian targets, conspicuously suggesting it may still be targeting the Ukrainian government.

A pro-Ukrainian hacking group calling itself NB65 allegedly took down the servers controlling Russian military satellites. This remains unconfirmed, but, if accurate, might also be interfering with the ability of western spies to keep an eye on Putin’s plans. Further evidence that vigilantes can often be a liability rather than an asset.

Pravda received a hacked list of 120,000 identities allegedly representing detailed information on most of the Russian military forces involved in the war. This information appears to be a true doxing, but it is unclear how old the information is and if it represents the people currently actively involved in the conflict.

In addition, Proofpoint published research showing an increase in phishing targeting NATO officials. This is a timely reminder that we all need to expect an increase in this type of attempted compromise, especially during conflicts like this.

[Update (2022-02-28)]: Monday, February 28 was another complicated and busy day for cyber-attacks, with more than its fair share of confusion. There were more alleged leaks, and factions chose sides. Hactivist supporters of Ukraine hacked into electric car charger stations to display messages offensive to President Putin.

A Ukrainian researcher publicly leaked the internal communications of the Conti ransomware group. We learned that the group’s primary Bitcoin wallet has had upwards of $2,000,000,000 USD deposited in the last two years and that loyalty is far less prevalent in the criminal underground than among the rest of us.

The good news so far? The Russians have not used cyber-attacks to destroy or disrupt basic services in Ukraine. Malware and cyber-destruction have been minimal. We shouldn’t rest on our laurels though. This situation is unlikely to resolve itself in a way that will lower the risk of online attacks.

[Update (2022-02-26 and 2022-02-27)]: Over the weekend of February 26 and February 27 a number of things happened.

On the afternoon of Saturday, February 26, Mykhallo Federov, the vice prime minister of Ukraine and its minister of digital transformation, sent out a tweet imploring people with cyber skills to join a virtual IT army to help Ukraine attack Russian assets in retaliation for the hacking attacks Russia has allegedly perpetrated toward Ukraine. An “IT Army” post on a message platform included a list of 31 targets for supporters to attack.

Many people want to support Ukraine, but I advise against doing something like this to show support. Unless someone is working directly on behalf of a nation-state, they are likely to be committing a serious criminal offence.

In addition, a cybersecurity researcher on the Ukraine-Romania border reported that Ukraine’s border control systems had been hit with wiper malware to disrupt the departure of refugees.

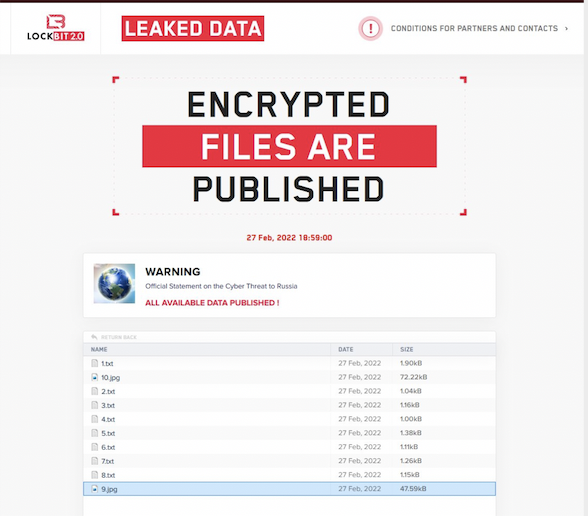

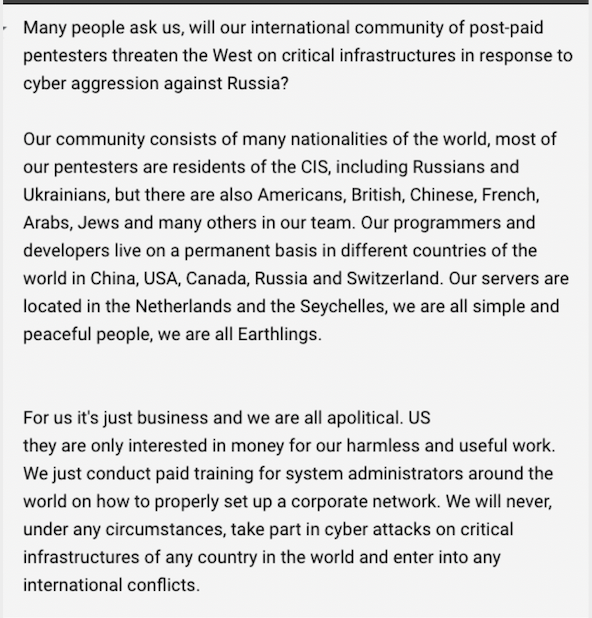

And another ransomware crew released an official statement regarding the conflict: Lockbit 2.0 posted a message to its dark web site saying that it will never attack the critical infrastructure of any country and is not taking sides. It claims to be just a diverse group of “post-paid pentesters,” and that it is just business and “all we do is provide paid training to system administrators around the world on how to properly set up a corporate network.”

The statement was posted in eight languages alongside two JPEG images of the earth.

[Update (2022-02-25)]: By February 25, 2022, the conflict had moved from purely cyber-attacks to a ground war, and we are seeing activity from non-state actors who could cause additional disruption and impact outside the conflict zone.

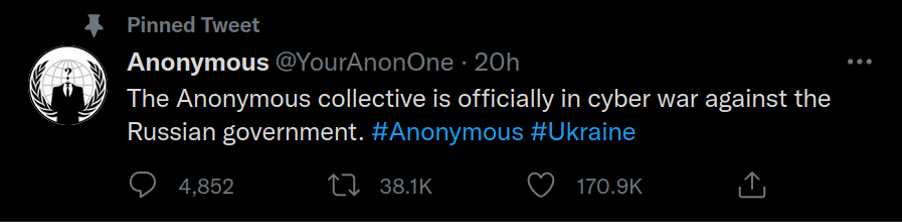

First, a Twitter account representing Anonymous, the freely associated group of hacktivists, declared “cyber war” against the Russian government.

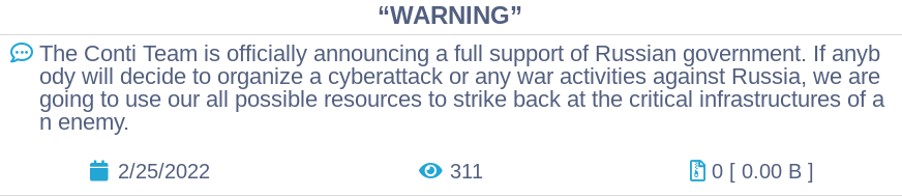

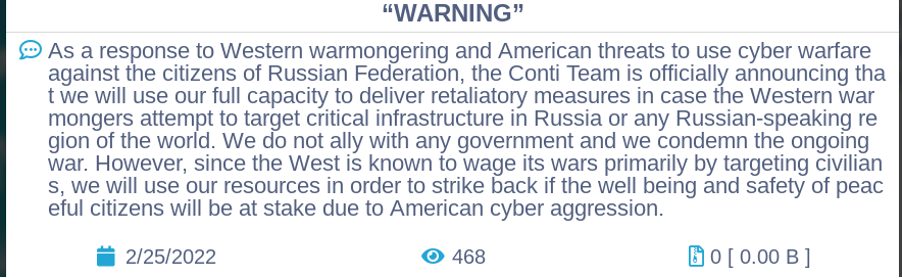

A few hours later, the prolific ransomware group, Conti, posted a message to their dark web site declaring their “full support of the Russian government.”

Both declarations increase the risk for everyone, whether involved in this conflict or not. Vigilante attacks in either direction increase the fog of war and generate confusion and uncertainty for everyone. The likelihood that other criminal groups based in the Russian theatre will ramp up attacks against Ukraine’s allies seems high.

By 20:00 UTC on February 25, Conti had deleted its previous statement, which appears to have been too antagonistic toward the U.S. Government. The new statement has lowered the tone a bit, suggesting they may only “strike back” in response to American cyber aggression.

Another group going by the name CoomingProject allegedly posted a similar statement saying, “Hello everyone this is a message we will help the Russian government if cyberattacks and conduct against Russia.” Their site is currently offline, and we were unable to confirm this post.

[Update (2022-02-24)]: At 02:00 local time on February, 24, 2022, the websites of the Ukrainian Cabinet of Ministers, and those of the Ministries of Foreign Affairs, Infrastructure, Education, and others were unreachable, according to CNN. By 06:00 local time on February 24, 2022, they appeared to be operating normally.

[Update (2022-02-23)]: On February 23, 2022 at around 16:00 local time in Ukraine, a wave of DDoS attacks was unleashed against the Ukraine Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ministry of Defense, Ministry of Internal Affairs, Cabinet of Ministers and the Security Service of Ukraine. The outages lasted about two hours and are so far unattributed. ESET and Symantec reported a new boot sector wiper being deployed at approximately 17:00 local time, which was precisely in the middle of this DDoS attack. It appears to have impacted a small number of organizations related to finance and Ukrainian government contractors. Symantec reported there was some spillover onto PCs in Latvia and Lithuania, likely remote offices of Ukrainian companies.