NASA scientist detained at US border until handing over PIN to unlock his phone

Credit to Author: Darlene Storm| Date: Mon, 13 Feb 2017 06:17:00 -0800

Sidd Bikkannavar understands that his last name may sound foreign, but he is a natural-born U.S. citizen who has been working at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab for 10 years. He was flagged by U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) for extra scrutiny when returning to the U.S. from Patagonia where his vacation consisted of racing solar-powered cars.

After his passport was scanned at George Bush Intercontinental Airport in Houston, Bikkannavar was detained by CBP until he handed over the PIN to his government-issued phone.

At first, the border agent asked him questions that CBP already knew the answers to since Bikkannavar is enrolled in CPB’s Global Entry program which gives “pre-approved, low-risk travelers” expedited entry into the U.S.; before being approved for the program, CBP says “all applicants undergo a rigorous background check and in-person interview before enrollment.”

Bikkannavar has traveled extensively, but he had not visited any of the countries listed in the immigration ban. Although he asked the CBP official why he was chosen for extra scrutiny, the agent refused to answer his question.

Then the border agent whipped out an “Inspection of Electronic Devices” paper and wouldn’t let him leave without giving CBP his PIN. Bikkannavar told The Verge, “I told him I’m not really allowed to give the passcode; I have to protect access. But he insisted they had the authority to search it.”

With PIN in hand, the CBP agent disappeared with the NASA-issued phone for 30 minutes.

Bikkannavar told the story in his own words on Facebook:

Sorry for the absence. On my way home to the US last weekend, I was detained by Homeland Security and held with others who were stranded under the Muslim ban. CBP officers seized my phone and wouldn’t release me until I gave my access PIN for them to copy the data. I initially refused, since it’s a JPL-issued phone (Jet Propulsion Lab property) and I must protect access. Just to be clear – I’m a US-born citizen and NASA engineer, traveling with a valid US passport. Once they took both my phone and the access PIN, they returned me to the holding area with the cots and other sleeping detainees until they finished copying my data.

I’m back home, and JPL has been running forensics on the phone to determine what CBP/Homeland Security might have taken, or whether they installed anything on the device. I’ve also been working with JPL legal counsel. I removed my Facebook page until I was sure this account wasn’t also compromised by the intrusion into my phone and connected apps.

After his phone was returned, Bikkannavar turned it off until he could give it to the JPL IT department. While he didn’t say what was on the phone, he did tell The Verge that the “cybersecurity team at JPL was not happy about the breach.” Since the incident, JPL has given Bikkannavar a new phone with a new number.

Bikkannavar said he doesn’t know why he was targeted for the electronic search, telling The Verge, “He understands that his name is foreign — its roots go back to southern India,” but he “didn’t think it would be a trigger for extra scrutiny.” He added, “Sometimes I get stopped and searched, but never anything like this. Maybe you could say it was one huge coincidence that this thing happens right at the travel ban.”

Yet CBP cannot legally require travelers to unlock their phones or other electronic devices. Hassan Shibly, chief executive director of CAIR Florida, told The Verge, “In each incident that I’ve seen, the subjects have been shown a Blue Paper that says CBP has legal authority to search phones at the border, which gives them the impression that they’re obligated to unlock the phone, which isn’t true. They’re not obligated to unlock the phone.”

Although it is troubling that one government agency would make another hand over the key to unlock secure government information, or that border agents demand for anyone to unlock their devices, there is nothing new about electronic devices being searched at the border without any reasonable suspicion. Back in 2013, the ACLU had already warned that two out of every three Americans had lost Fourth Amendment protections to DHS.

Last week, John Kelly, the head of DHS, said if foreigners want to set foot on U.S. soil, then they need to hand over their social media passwords as part of the vetting process for visa applicants. “If they don’t want to give us the information, then they don’t come.”

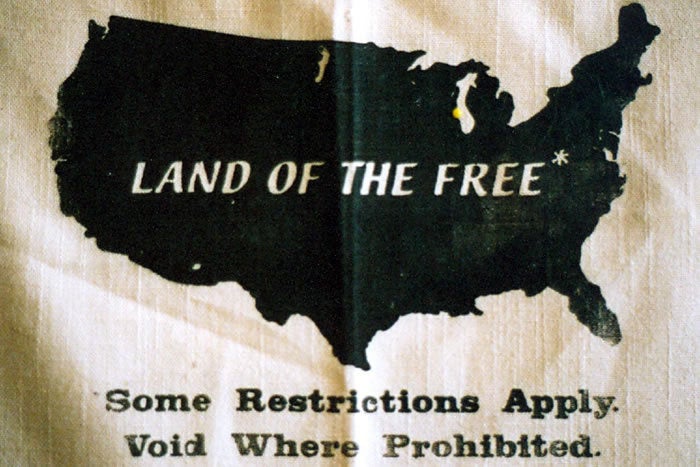

Welcome to the land of the free.